Melissa Brunner. Interview with the artist

Written by David Knoll

7/8/2023

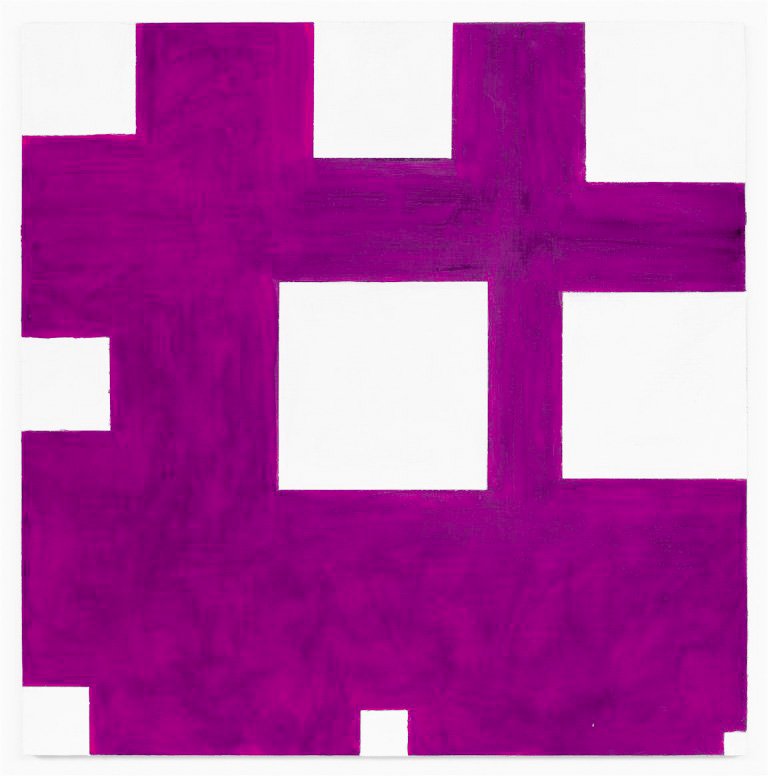

Melissa Brunner. Untitled, 2015, acrylic on canvas

David Knoll: So you were just starting back then and you’d just finished your education, what kind of paintings were you making then?

Melissa Brunner: I was just starting, I had a studio in Kolomna … Well, actually, I spend a lot of time thinking before I do anything.

D.K.: Planning the paintings or thinking about ideas?

M.B.: Not planning the paintings, but mostly figuring what I didn’t want to do.

D.K.: There’s so much not to do!

M.B: That’s the main thing. Once you figure that out, you have a chance, right?

D.K.: I often think about what to leave out—how do you distill something to the most essential quality or qualities? I think that’s what drew me to your work initially, is that I feel like it’s really doing that, getting at something essential but doing it in this really interesting and fresh way. It’s very hard to do as an artist. But back to the studio in Kolomna, what were you making then?

M.B: Well, I did some paintings which were one color, which was very difficult because everybody was opposed to it.

Melissa Brunner. Music of Geometry, 2015, acrylic on canvas

D.K.: Just one solid color?

M.B.: Yeah, but some are in separate parts.

D.K.: So you were already on that trajectory—making the kind of paintings you would first show in Moscow?

M.B.: Yeah.

D.K.: So then you were in Moscow starting from that point?

M.B.: Yes.

D.K.: And you maintained a studio in the city ever since?

M.B.: Well the great thing about Moscow is you’re always leaving, because it’s so intense, you know.

D.K.: Do you make sketches before you make a painting?

M.B.: I do it in my head.

D.K.: Planning the paintings, including the mathematical concepts?

M.B.: Everything, yes.

D.K.: Then when it comes time to apply the paint, do you have a system for drawing before you paint?

M.B.: Well, I draw it out in pencil and paint it in.

D.K.: Are they based on grids?

Melissa Brunner. Untitled, 2017, oil on canvas

M.B.: Sometimes—it might end up looking like a grid, but that’s not how I arrive at it. I’ve studied a lot of geometry so this stuff is very easy—and making a painting has its own problems, but making a drawing is as much work as making a painting so I don’t do a preparatory drawing—there are drawings but they happen after the painting. But once you change the medium then everything completely changes because making a painting is very different from working on a piece of paper. I’ve made a lot of prints…

D.K.: What was the impact of having the first show? Were things different for you?

M.B.: To me, you just do the stuff, and you find yourself in a continuum and you’re not looking around at what’s going on… I got a lot of attention though, because of the show.

D.K.: I feel like one thought can change your whole life. In a small way—in a subtle way, who knows?

M.B.: It all adds up.

D.K.: This pattern, which is mathematical, recurs a lot in your work…

Melissa Brunner. Untitled, 2019, acrylic on canvas

M.B.: It’s just a simple progression –N+1 1,2,3,4 and then when it crosses itself it makes all that stuff you know.

D.K.: So it increases in size exponentially.

M.B.: The copper one is geometric so it doubles.

D.K.: There’s a logic to it right?

M.B.: Yep. It’s a progression. It goes around the edge then it goes in the center, so it’s actually squares that have a squared off spiral, that’s how it works. And I like those things because it does things that I would never think of.

D.K.: Just naturally, based on it’s own logic. And these ones as well? Is there a progression?

Melissa Brunner. Untitled, 2019, acrylic on canvas

M.B.: A pattern—radiating lines, you know.

D.K.: That design—were you thinking about anything in particular when it came to making that?

M.B.: Cultures around the world use it—and archaeologists called it a rayed sun—they draw a circle with radiating lines around it. So I would see those and I thought that was kind of interesting. So I would see those but not draw the circle, you know. Making the lines radiating out with no circle. Then I decided to make the lines oblique, and not straight out, and I ended up making a bunch of them.

D.K.: You’re tapping into something bigger it seems.

M.B.: 200 years ago, I’m glad we agree. [Laughter]

Melissa Brunner. The Sun, 2020, acrylic on canvas

D.K.: That’s a great design though. I can see why you kept going back to it, because it seems quite open in a lot of ways. It could be seen as representational…

M.B.: To others. Somebody called it a depiction of the sun, so I jumped down their throat, you know. [Laughter]

D.K.: [Laughter.] Of course! I get why you’re opposed to any interpretation of your work that isn’t open. I can also understand your resistance to classification, identification, or even talking about it.

Melissa Brunner. Spiral, 2019, oil on canvas

David Knoll has published widely on international modernism and in 2011 was a Centre for Curatorial Leadership Fellow. From 2017-21, in addition to his role in the department, he served as Curator in Charge of the Leonard A. Lauder Research Centre for Modern Art and now sits on the Advisory Committee. David holds a Ph.D. from the University of Aberdeen.